Students queue to wash their hands at the courtyard of a school in Port Sudan city, eastern Sudan, on Feb. 26, 2025. (Photo by Fayez Elzaki/Xinhua)

KHARTOUM, June 1 (Xinhua) -- Thirteen-year-old Muayad Kamel weaves through the central market in southern Khartoum, clutching a small plastic box filled with rosaries, tissues, and masaweek -- teeth-cleaning twigs. Each step reflects a burden far too heavy for someone his age.

The market, centered around a once-bustling bus station, was slowly stirring back to life, humming with vendor calls and the steady buzz of generators -- the only source of electricity. Kamel slips quietly between the idle vehicles, moving through rows of half-loaded buses. He lifted his box toward the windows, calling out his wares, his voice barely audible.

A fine layer of dust coats his face and clothes, worn thin by long days in the heat. "I used to be one of the top students," he said softly, when asked why he left school. "But now I have to help my family."

His father is sick. He has younger siblings. Kamel works over 10 hours a day, arriving early and leaving before sunset. On a good day, he earns around 5,000 Sudanese pounds (less than 2 U.S. dollars).

"This isn't enough for more than a simple meal of fava beans for the family," he said, wiping sweat from his brow. "But I'm glad I can help. I just hope this nightmare ends, and we can return to a normal life," the boy added with a faint smile.

Behind that smile lies a quiet sorrow, shared by countless Sudanese children whose lives have been upended by the ongoing war between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces.

As the conflict stretches into its third year, children are paying a heavy price, as their lives, education, and hopes for the future hang by a thread. According to a report by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) released on April 15, the number of children needing humanitarian aid has doubled from 7.8 million in early 2023 to over 15 million in 2025.

In a makeshift school established by activists in Khartoum's Al-Inqaz neighborhood, 10-year-old Muram sits on the ground, carefully drawing a dove in her notebook. "I learned that the dove is a symbol of peace, and I pray that peace will spread across our country and that life will return to normal," she said, her voice brimming with hope.

Muram is one of about 15 children attending the temporary school, a modest effort to restore a sense of learning and routine after education was abruptly halted by the outbreak of conflict in mid-April 2023.

With no desks or chairs and barely any materials, the school relies on improvised methods to get by, a reflection of the wider economic struggles. Still, Muram beams at the chance to learn again. "I lost my school bag, books, and pens because of the war," she said, "but I'm happy to be back in school."

Muram misses the friends and classmates she left behind at her original school. "Many of my classmates were displaced to other areas and now live in camps," she said. "The war took away our dreams of learning and forced us from our homes."

"More than 17 million children are entirely out of school because of the war and its devastating impact," said Abdul Qadir Abdullah Abu, secretary-general of the Sudanese National Council for Child Welfare.

"Millions are without education or shelter, while others are displaced and living as refugees," Abu told Xinhua.

He estimates around 8 million children are displaced within Sudan, and another 1.5 million have fled as refugees.

According to UNICEF, Sudan is grappling with the world's largest child displacement crisis, putting the future of its 24 million youngest citizens at risk.

At a displacement camp in Port Sudan, currently serving as Sudan's temporary capital, 11-year-old Kamal tried to play a musical instrument provided by a local band during a rare recreational event for children.

Though he tried to hide it, sadness was plain on Kamal's face. His fingers trembled over the instrument, betraying the tension and fear weighing on his young mind.

"I don't feel at home here," Kamal said quietly. "We had a lovely house in Khartoum, and I wish we could go back."

Kamal now lives with his mother and brothers in a camp set up inside a school in Port Sudan's Al-Sika Hadeed neighborhood. His father passed away several years ago.

Although the family has been here for over a year, Kamal still hasn't adjusted, describing the place as "strange and desolate."

"There's no playground here, and my mother won't let me go outside. I feel trapped," he said.

Living in displacement camps poses serious challenges for children, said Sudanese psychologist Ibtisam Al-Tayeb. "The spaces are extremely cramped, with three or four families often forced to share a single room or classroom," she explained.

"Growing up in displacement camps leaves lasting marks on children's behavior, thinking, relationships, and mental well-being," she told Xinhua.

"We fear that the future of these children will be shaped by a legacy of ignorance, violence, and displacement, a burden that could weigh heavily on generations to come," she noted. ■

Children have fun at a play room inside a school in Port Sudan city, eastern Sudan, on Feb. 27, 2025. (Photo by Fayez Elzaki/Xinhua)

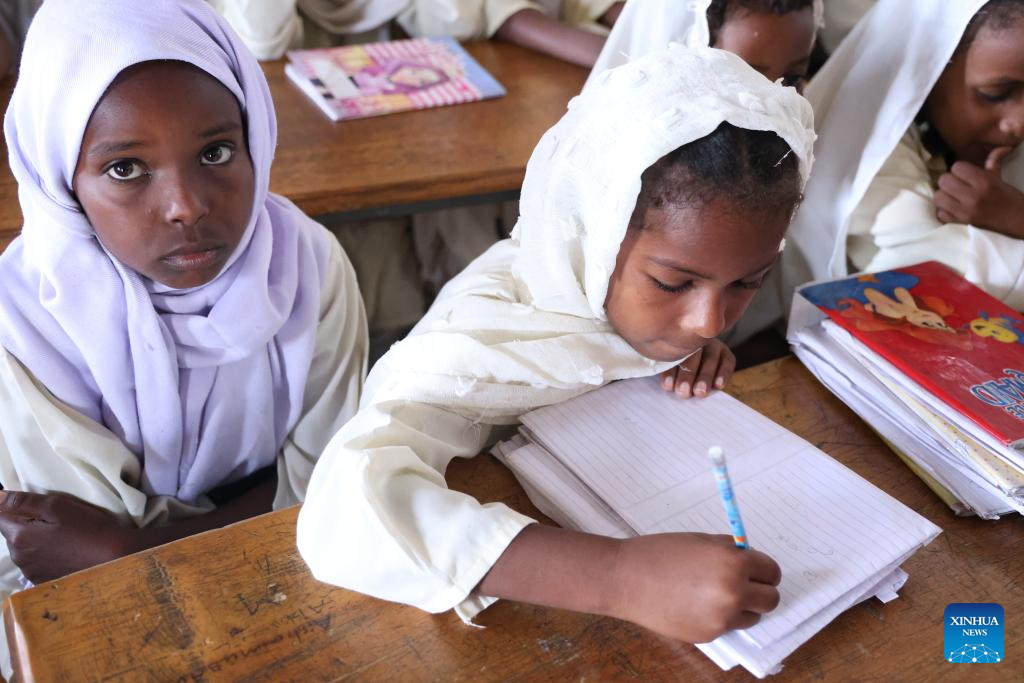

Children are pictured inside a classroom at a school in Port Sudan city, eastern Sudan, on Feb. 27, 2025. (Photo by Fayez Elzaki/Xinhua)

A student writes on a notebook inside a classroom at a school in Port Sudan city, eastern Sudan, Feb. 27, 2025. (Photo by Fayez Elzaki/Xinhua)

This photo taken on Feb. 27, 2025 shows children having snacks at the courtyard of a school in Port Sudan city, eastern Sudan. (Photo by Fayez Elzaki/Xinhua)

Students are pictured inside a classroom at a school in Port Sudan city, eastern Sudan, on Feb. 27, 2025. (Photo by Fayez Elzaki/Xinhua)

Students walk in line as they leave their school in Port Sudan city, eastern Sudan, on Feb. 26, 2025. (Photo by Fayez Elzaki/Xinhua)

This photo taken on Feb. 27, 2025 shows a mother escorting her disabled daughter to school in Port Sudan city, eastern Sudan. (Photo by Fayez Elzaki/Xinhua)